EEA Newsblast: ICILS study results

Successes and Surprises:

How European countries are responding to the ICILS results

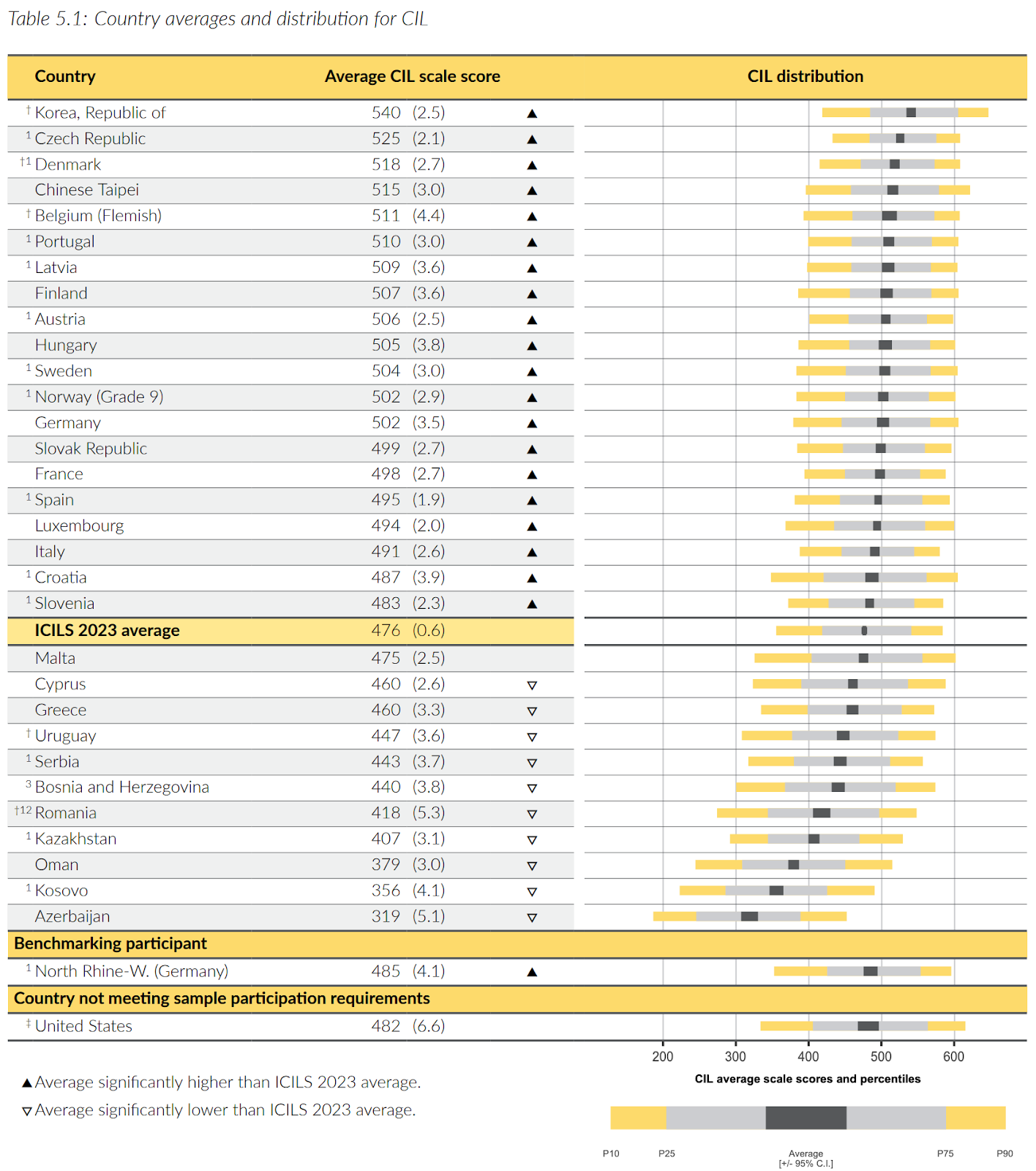

The most recent results from the 2023 International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS) reveals a complex landscape of digital literacy across 35 education systems internationally. ICILS is an international, large-scale assessment that focuses on digital literacy education by assessing eighth grade students. Conducted every five years, the study monitors students’ Computer and Information Literacy (CIL) and Computational Thinking (CT) being able to address achievement over time. The 2023 ICILS study collected high-quality data from more than 130,000 students and more than 60,000 teachers.

The results from the 2023 study show that eighth-grade students around the world are using Information and Computer Technology (ICT) more and more as the years progress, but digital literacy achievement scores have not been increasing to match(1). Whilst we must take the period of global lockdowns and challenges associated with the pandemic in 2020 and 2021, the study highlights not only the differences in digital literacy, but also showcases each country’s unique attitudes and approaches toward ICT in education. The study therefore offers valuable insights into the challenges and next steps for their respective educational systems.

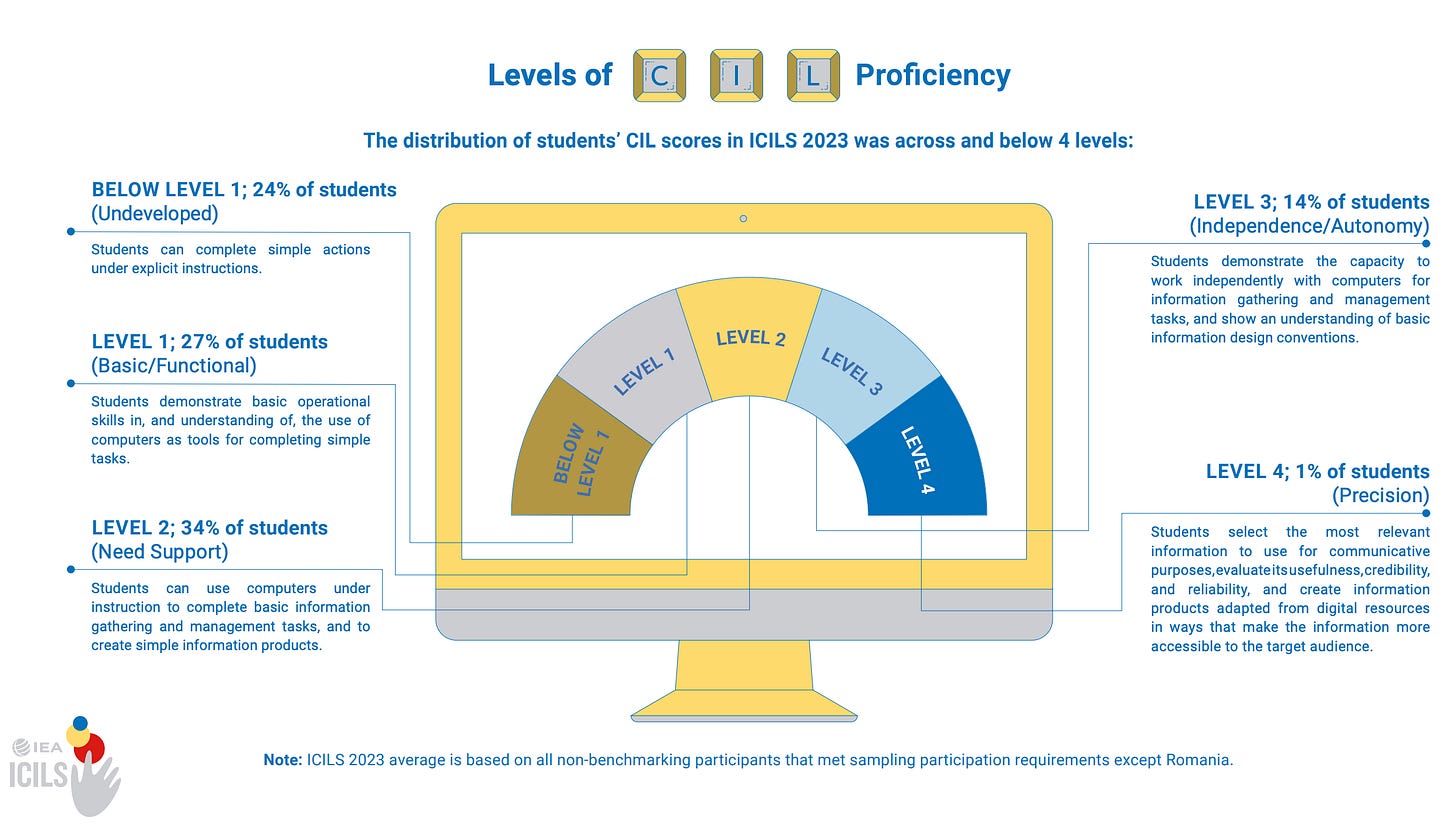

Some of the key international take aways include the fact that female students outperformed male students in CIL globally, while generally CIL skills decreased between 2013 and 2023, the digital divide remains prominent, more than half of all students on average are operating below proficiency at a very basic level, and students are learning about internet-related topics more frequently outside of school(2).

Participating again this year were Chile, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany (as a benchmarking group), Italy, Kazakhstan, Republic of Korea, Luxembourg, Portugal, Uruguay and the United States. Participating for the first time and enabling a broader, international comparison were Austria, Azerbaijan, Belgium (Flemish), Bosnia and Herzegovina, Chinese Taipei, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Oman, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden.

The EEA is not only interested in the results, but also in the reactions that are shown to them, the way in which countries and ministries are planning on addressing some of the main issues, and higher-level connections that can lead to supranational recommendations. Below, we comparatively explore some of the reactions and results of ICILS 2023 with a focus on Europe.

The use of ICT and provision of digital infrastructure

One important cultural element to consider when evaluating the results are the differences in access and their impact on the 2023 study. Leading far above the international average, South Korea attributes their outstanding ICILS results to a strong commitment to integrating ICT in schools and at home as well as the students’ relatively unrestricted access to digital devices outside of school supplemented with robust digital citizenship programmes(3).

Conversely in Spain, reports suggest a correlation between their positive results and the fact that Spanish parents tend to restrict screen time of their children on school days more than other European parents(4).

Similarly, there seems to be a direct correlation between access to technology and their results in most countries. Those with strong educational infrastructures and early integration of ICT in curricula tend to perform better. For Finland, Denmark, and the Netherlands this trend suggests that well-developed infrastructure and early ICT exposure may contribute to higher digital literacy levels. Others, like France, reported proudly that students' performance in digital literacy was less linked to access to certain IT resources than in other countries(5).

In Hungary, students with more or consistent access to a computer for schoolwork scored significantly higher, suggesting additionally that the role of family support is important, and perhaps reflecting the country's strategic investments in digital education between 2017 and 2020(6). This is interesting in the face of the digital bans that Hungary put in place this summer(7).

Challenges for students

Flemish students in Belgium rank among the top in digital literacy, only slightly behind countries like South Korea, Taiwan, and the Czech Republic(8). However, notably, a significant portion of students struggle to critically assess online information. In fact, despite the impressive results, three-quarters of Flemish students find it difficult to navigate online texts critically, an area of concern given the increasing importance of digital literacy in information evaluation(9). Furthermore, 67% of Flemish students admitted to multitasking—such as texting or watching videos—while studying(10). This has led Flanders news to claim that Flemish pupils excel in their computer skills, but are consuming too much online(11).

Spanish reports are celebratory and claim that “Spanish students handle computers better than their European peers(12).”However, Spanish students still lag behind leading nations like South Korea by the equivalent of nearly a full school year.

Generally, a number of European countries showed a downward trend in their scores. The majority of countries with results which declined or were showing tendencies towards lower percentages of competencies were quick to suggest that these results were completely in line with the international average in order to relativise the outcomes. For example the French national ministry of education states: “Student results in France are in line with the European Union average in digital literacy and higher in computational thinking”(13).

Similarly, Latvian reports state that their low computer literacy scores are comparable with Finland and Hungary whilst their overall scores are higher than the international average(14).

These results must be a call to action and an opportunity to learn from each other as we explore solutions addressing the general increase in use of technology with a decrease in skills for practically engaging with issues like disinformation or targeted campaigns.

The myth of the digital native and a focus on language support

In Austria, news reports on the ICILS results, classified them as ‘sad’ and challenged the notion of "digital natives" stating that “just because young people use their mobile phones intensively every day, for example, does not mean that they are also acquiring the digital skills required for the 21st century (15).”

This sentiment is echoed by Norway’s director of the directorate of education saying, “today's youth live digital lives. But that does not mean that they have mastered the computer as a tool (16).” Statements from the German release of the ICILS report take this further this by claiming that “40% of the youth can only click and swipe (17)”.

The languages spoken at home, if they were not the language of the country, also seemed to make a significant impact on these social differences in multiple countries. For example, educational inequality is discussed as a major issue, particularly affecting students from migrant backgrounds or those who do not speak the respective country’s main languages at home.

A widening digital divide and significant gender differences

The ICILS results also highlighted the impact of socioeconomic factors on digital competencies and a widening digital divide in some countries. Italy, for example, whilst boasting a result higher than the international average, shows enormous differences and a significant divide between the north and the south of the country (18). Austria also found the differences between states to be greater than those between the nation as a whole and neighbouring countries (19).

Slovenian educators have shown concern about the growing disparity among students based on socioeconomic background, though differences between schools remain minimal. This stability in school equality is seen as a positive aspect, suggesting that Slovenia has a relatively equitable educational system despite the overall decline in competency scores. The high level of equity of the Spanish school system stands out, with fewer differences in the results showing between rich and poor (20).

Norway, known for its ambition to be the most digital country globally by 2030 (21), has been confronted with 40% of ninth graders scoring at the lowest levels of digital competence. Despite students’ high rates of digital use, their skills are declining, especially among those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Norwegian policymakers emphasise the need for planned, quality digital education rather than unstructured access to technology (23).

Sweden reflected these numbers with four out of ten students lacking the ability to evaluate the credibility, relevance and usefulness of information - a skill set fundamental to safe digital citizenship and participation (24).

In the majority of participating countries, girls outperform boys in digital literacy, with some reports suggesting this is due to the large amount of text used in these questions (25). This gap, however, is generally inverted when it comes to the scores for computational thinking. It will be important to understand the factors influencing these differences and implement ways of creating more equality and ensuring the gender and socioeconomic divides don’t deepen.

The important role of teacher satisfaction and preparedness

An indicator of success in achieving a high score for the study seems to be the level of satisfaction that teachers have with ICT resources and support. For example, only 13% of Czech teachers feel they lack technical support, and a mere 22% report insufficient equipment—remarkably low numbers compared to international averages displayed in the ICILS report (26).

Reflecting a paradox where digital readiness and scepticism coexist and despite the optimism regarding ICT infrastructure, Czech teachers remain divided on the educational impact of technology. Many are sceptical about ICT’s influence on learning, with three-quarters suggesting it may harm students' written expression and encourage shallow engagement through copying. Interestingly, only half of Czech teachers believe that ICT improves academic performance (27).

Looking forward in reaction to the results

Moving forward, a common theme is emerging: the need for strategic, well-planned digital education policies that transcend simple technology integration, aiming instead to foster critical, applicable digital skills across diverse student and educator populations. This is reflected in the reactions of multiple countries. Although the results have only just come out, some countries have already made suggestions for necessary changes.

For example, Norway’s Minister of digitisation, citing a need for a balanced approach and to improve access to future work environments, are calling for a new subject just focussing on technology and related skills (28). In the Flemish education system, on the other hand, whilst also addressing the need for increased skills acquisition, there is a call to approach the issues they have identified by integrating critical digital literacy and computational thinking more deeply into the curriculum, to focus on support through ICT infrastructure and policy, and providing targeted support for students from non-Dutch-speaking households (29).

Similarly, in Austria, strengthening digital competencies within the curriculum and teacher training programs to ensure teachers can teach these topics masterfully are seen as the lever to improvement (30). Addressing these gaps, Austria intends to prioritise digital literacy in teacher education and move away from assumptions about inherent digital skills among young people.

In Sweden, the School Minister’s response to the poor results for Swedish students is to focus on basic skills first "Digital competence requires that students have basic skills such as reading, writing, and arithmetic. Schools must set the right priorities; we need to focus on foundational skills first before students can develop digital competence (31)." In response, the Swedish EdTech Industry states that to develop digital competence requires purposeful and well-structured instruction and to achieve this, both short-term and long-term plans are needed (32).

In proactively identifying possible areas for development, Germany’s educators and policymakers are prioritising the integration of digital skills training for students, with suggestions of modernising classroom technology and improving teacher support. Furthermore, there is a discussion around bridging the gap between students’ everyday digital experiences and their formal education by creating relevant, modern learning environments that better prepare students for a digital world (33).

It will be imperative to develop systems that enable teacher preparedness and satisfaction, focus on skills development, look into decreasing the digital divide and socioeconomic issues as well as identifying pathways towards equality in systems. It is essential that our students and educators feel empowered in their use of digital technologies and ability to feel safe in their use. Otherwise, the European skills goals set in the European Commission’s Digital Education Action Plan to have a maximum of 15% of 14 year olds below competence level two as it is described in ICILS appear very far away.

Read the full international report on ICILS here.

Find the national reports on the outcomes relative to individual countries here.